ESG Report 2023

Environment

Energy

The way in which Alamos consumes energy plays a key role in the effectiveness of our Climate Change strategy, influences Air Quality and represents a significant proportion of our operating costs. We consume energy primarily through electricity use and fossil fuel combustion (diesel, gasoline, propane and natural gas).

Electricity is primarily used by our crushing and milling operations, underground ventilation, and in material handling. At the Young-Davidson and Island Gold mines electricity is sourced from Ontario’s low-carbon grid system, which is 71% comprised of renewables and non-emitting sources such as hydro, nuclear, wind, and solar1. While our Ontario sites benefit from this clean supply, Alamos does not hold a Power Purchase Agreement with the Province and therefore cannot claim procurement of renewable energy (as seen in Table 5.1). At the Mulatos mine, the construction of an electrical transmission line has been completed. Once connected to the Mexico grid (projected in 2024), Mulatos can transition away from its use of diesel generators for electricity production.

At our three operating mines, light vehicles are fueled by gasoline while heavy vehicles use diesel. At our Canadian mines, Young-Davidson and Island Gold, a portion of the diesel blend used for heavy vehicles is biodiesel – which, in comparison to petroleum diesel, emits less air pollution and is less toxic in the event of a spill. Historically, propane gas has primarily been used in Canada to heat our buildings and underground mines in the winter. After transitioning from propane at the end of 2022, Young-Davidson now uses compressed natural gas (CNG) for heating — which emits fewer greenhouse gases on a per-gigajoule basis. Island Gold is exploring the feasibility of implementing CNG at their operation.

In 2023, our sites took steps towards alignment with Alamos’ Energy & Greenhouse Gas Management Standard, which provides our mine sites with direction on managing energy use, preparing an Energy Management Plan, and implementing the Plan to focus on energy reduction. All our mines are encouraged to set site-specific targets for reducing total energy usage, and each site completed projects to support these goals during the reporting year. Young-Davidson progressed the implementation of their Ventilation-On-Demand project (which will automate mine ventilation fans to operate only when necessary) by adding two fans to the system – leading to savings of 580 GJ for the year. The mine also saved 234 GJ through LED lighting retrofits, and completed purchasing for a compressor waste heat recovery project that will reduce the energy used for incoming water heating by approximately 7,500 GJ. The Island Gold mine completed a Compressed Air Efficiency project, wherein each air compressor was outfitted with a zero-loss drain and an individual meter to measure energy use and other relevant indicators. The project is on track to save approximately 5,934 GJ annually. The Mulatos mine installed LED lightbulbs and solar-powered lighting throughout the mine camp and office spaces. More significantly, the La Yaqui Grande (LYG) site completed its powerline connection to the Mulatos site and electrical network, which enables both locations to draw energy from Mulatos’ power generation units and, eventually, the Mexico electricity grid. Having both sites draw power from Mulatos’ generator sets improves the efficiency of electricity generation and allows for the removal of LYG’s generator sets.

Energy Consumption2 (GJ)

Table 5.1

| Type Consumed | Alamos Total | Young-Davidson | Island Gold | Mulatos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel Consumption | ||||

| Heavy Fuel Oil3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Petroleum Diesel | 1,722,991 | 140,100 | 211,308 | 1,371,583 |

| Biodiesel | 18,689 | 8,488 | 10,201 | 0 |

| Gasoline | 42,583 | 2,124 | 14,406 | 26,053 |

| Propane Gas4 | 147,654 | 0 | 72,011 | 75,643 |

| Naphtha | 6,344 | 6,344 | 0 | 0 |

| Compressed Natural Gas5 | 221,612 | 221,612 | 0 | 0 |

| Renewables | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2,159,872 | 378,667 | 307,926 | 1,473,279 |

| Electricity6 Consumption | ||||

| Electricity Generated | 193,785 | 475 | 717 | 192,593 |

| Renewable Electricity Purchased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-Renewable Electricity Purchased | 1,295,718 | 960,748 | 334,179 | 791 |

| Total Energy Consumption7 | ||||

| Total | 3,455,590 | 1,339,415 | 642,105 | 1,474,070 |

| Portion of Total Supplied from Grid Electricity | 37.5% | 71.7% | 52.0% | 0.1% |

| Portion of Total from Renewable Sources | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Energy Consumption (GJ)

Figure 5.1

Young-Davidson

Island Gold

Mulatos

Energy Intensity Ratios8 (GJ)

Table 5.2

| Energy Intensity Ratio | Young-Davidson | Island Gold | Mulatos | Alamos Total: 2023 |

Alamos Total: 2022 |

Alamos Total: 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy per Tonne of Ore Mined | 0.47 | 1.47 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.57 |

| Energy per Tonne of Ore Treated | 0.47 | 1.46 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.35 |

| Energy per Ounce of Gold Production | 7.24 | 4.89 | 6.93 | 6.53 | 7.78 | 7.97 |

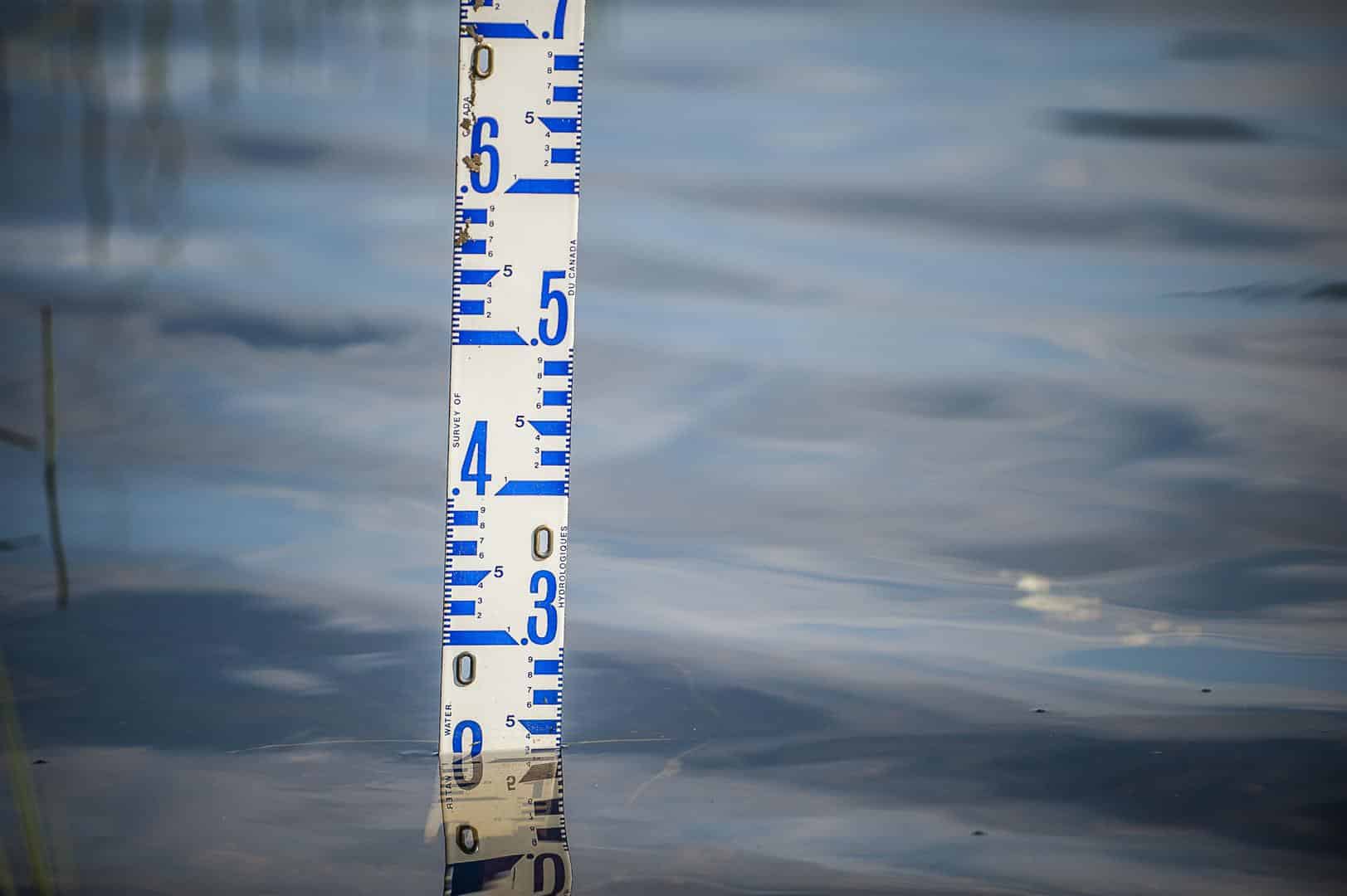

Water

OUR COMMITMENT

Water plays a central role in every aspect of the mine life cycle. From localised water use during exploration to the management of final effluents throughout operations and closure, the state of water quality and quantity is integral to the way we do business. Water is also a valuable source of sustenance and an otherwise significant resource for many Indigenous communities. In recognition of these compounding factors, Alamos is committed to collaborating with stakeholders to better manage our water use.

Alamos employs a number of systems to help us identify and minimise water-related impacts. Our company-wide Water Management Standard provides sites with guidance for implementing effective water management practices, covering the withdrawal, use, storage, recycling, treatment and discharge of water. The purpose of the Standard is to define site requirements for developing proper water monitoring and control plans to reduce potential effects on the environment while meeting all jurisdictional requirements. We also maintain comprehensive surface and ground water monitoring programs at all of our sites. Numerous locations at each site are monitored routinely to assess the state of water quantity (through the assessment of water levels, flow velocities, and other hydrological indicators) and water quality (through external laboratory analysis of grab samples for a broad suite of analytes). Further, comprehensive reviews of site-wide water balances and water management facilities take place at each of our operations.

Company-Wide Water Interactions

Table 5.3

| Water Interaction Type | 2023 | 2022 | 20219 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Water Withdrawn (ML) (water taken from the environment) |

6,177 | 6,496 | 4,871 |

| Total Water Discharged (ML) (water released to the environment) |

3,282 | 3,051 | 1,798 |

| Total Water Treated (ML) | 2,671 | 1,708 | 1,414 |

| Total Water Consumed (ML) (= withdrawals – discharges) |

2,895 | 3,445 | 3,073 |

| Total Water Recycled/Reused (ML) (water used from on-site stores) |

3,683 | 2,041 | 3,573 |

| Total Water Used (ML) (= consumed + recycled) |

6,578 | 5,486 | 6,645 |

| Portion of Water Recycled/Reused (= recycled / used) |

56% | 37% | 54% |

| Total Water Intensity (m3/t) (= consumed / tonne of ore treated) |

0.25 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

In 2022, Young-Davidson reported the volume of rain and snowmelt for the first time. This has created a significant increase to the site-level and company-wide figures for water withdrawals, in turn influencing the values of water consumption, use, intensity and the portion of water recycled. This information is unavailable for prior years, thus the year-on-year comparisons in Table 5.3 and Figures 5.2 and 5.3 have been impacted such that 2021 values for the above-mentioned indicators appear lower.

Throughout their life cycle, each mine operation moves through various phases of water requirements. Volumes of water withdrawals, discharges, storage, treatment, consumption, and use are constantly in flux (as demonstrated by the high variability of water intensity values in Figure 5.3). Alamos has not yet set company-wide water-related objectives and targets. Objectives for maximised water reuse and recycling are set by each of our mines individually.

Company-Wide Water Interactions

Figure 5.2

Water Consumed per Tonne of Ore Treated10

(By

Site)

Figure 5.3

YOUNG-DAVIDSON

The Young-Davidson Mine predominantly interacts with the nearby Montreal River; freshwater is withdrawn from an upstream portion, and treated effluent is discharged to a downstream portion. The river is not considered an area of water stress or a listed conservation area, but is of high importance to local Indigenous Peoples. Groundwater withdrawals also occur at the Young-Davidson Mine, as water is pumped out from the underground mine workings to allow safe operations. In 2023, water withdrawals from underground and surface sources totaled to 2,879 ML (including rain and snowmelt), and discharges totaled to 1,089 ML – both less than 5% of the annual average volume of the water body. All water discharged to the Montreal River must first be processed by the mine’s extensive water treatment system. Underground mine water is pumped to surface and treated through a Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor (MBBR) which is responsible for the biological aerobic destruction of ammonia, with an additional chemical dosing system for the precipitation of metals. Surface contact water from the tailings facilities is sent to the water treatment plant where it undergoes pre-treatment (first agitation with hydrogen peroxide, ferric sulfate, and lime; then clarification) before being passed through the Submerged Aerobic Growth Reactor (SAGR) which addresses ammonia and residual metals. Once the treated effluents of the MBBR and SAGR are deemed to be of suitable quality, they are directed to the mine water settling pond prior to discharge through a buried pipeline. The list of priority substances of concern for which discharges are treated has been guided by the Metal and Diamond Mining Effluent Regulations (MDMER). This regulation sets effluent concentration limits for arsenic, copper, cyanide, lead, nickel, zinc, suspended solids, radium 226, and un-ionized ammonia. The MDMER also requires Environmental Effects Monitoring studies, which include the analyzation of an additional 19 parameters such as chromium, iron, mercury11, and selenium. The site also has a provincially regulated Environmental Compliance Approval (ECA) for water discharge to the environment.

Young-Davidson had two non-compliant water discharges in 2023 for the exceedances of Total Suspended Solids (in June) and mortality of Daphnia Magna (water fleas) in October. In both cases, the source of the issue was promptly identified and remediation measures were applied.

2023 Young-Davidson Water Consumption

Table 5.5

| Consumption | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Water Consumption (ML) | 1,791 |

| Water Intensity (m3/t)15 | 0.62 |

ISLAND GOLD

The Island Gold Mine’s domestic water is sourced from Maskinonge Lake, while discharges are directed to Goudreau Lake. Neither water body is considered an area of water stress or a listed conservation area, but both have been deemed of high importance to local Indigenous Peoples. Groundwater withdrawals also occur at Island Gold, as water is pumped out from the underground mine workings to allow safe operations. In 2023, 944 ML of water was withdrawn from Maskinonge Lake and underground sources, and 1,429 ML was discharged to Goudreau Lake – with both indicators equating to less than 5% of the annual average volume of the respective water body. Given that more water was discharged than withdrawn, Island Gold reports a negative water intensity. To protect the water quality of Goudreau Lake amongst these discharges, the mine uses semi-passive water treatment methods. Effluents are treated in holding ponds, where solids are removed by coagulation and flocculation, Cyanide is naturally degraded, and acidity (pH) is chemically regulated prior to discharge. The Island Gold Mine is also subject to the MDMER and an ECA, which guides the priority substances of concern for treatment. There were no unplanned water discharges throughout the year at Island Gold, and no instances of non-compliance with discharge limits.

2023 Island Gold Water Consumption

Table 5.7

| Consumption | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Water Consumption (ML) | -485 |

| Water Intensity (m3/t)19 | -1.10 |

MULATOS

The Mulatos Mine (including La Yaqui Grande) withdraws surface water from the Mulatos River, and groundwater from the Yécora aquifer. Ten protected species can be found in the Mulatos River, however, the mine withdraws less than 5% of the river’s annual average volume (a total withdrawal of 2,354 ML in 2023), thus the area is not significantly impacted. Mulatos discharged a total 765 ML of water during the year, to two separate destinations: domestic sewage is discharged to the Los Bajos Creek (after undergoing biological treatment via activated sludge), and all other contact water receives a lime-based chemical precipitation treatment (which balances pH and removes heavy metals and sulfates) prior to being discharged to the Mulatos Creek. The list of priority substances of concern for which discharges are treated are determined by the Mexican Official Standard NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021, which establishes maximum allowable limits for pollutants in wastewater discharges into national receptive bodies. For mining-related discharges, Mulatos pays particular attention to cyanide, heavy metals, and parameters contributing to acidity. For domestic sewage-related discharges, treatment focuses on biological parameters. There were no unplanned discharges throughout the year at Mulatos, and no instances of non-compliance with discharge limits.

According to Aqueduct20 (the World Resources Institute’s Water Risk Atlas tool), the Mulatos Mine is located in an area with extremely high baseline water stress. Given its limited availability, the mine takes care to consume no more water than is necessary. Note that the mine is also managing the added challenge of Acid Rock Drainage (Table 5.10) due to the natural geology of the landscape, and as such, a significant portion of withdrawn water must be stored on site prior to being safely released through evaporators or following treatment by the site’s water treatment plant. Stored water accounts for much of the volume that has been withdrawn and not yet discharged (Table 5.8).

2023 Mulatos Water Consumption

Table 5.9

| Consumption | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Water Consumption (ML) | 1,589 |

| Water Intensity (m3/t)24 | 0.19 |

Acid Rock Drainage

Table 5.10

| Status | Young-Davidson | Island Gold | Mulatos |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted to Occur | False | False | True |

| Actively Mitigated | False | False | True |

| Under Treatment/Remediation | False | False | True |

Waste

The safe storage, handling, and disposal of all types of waste is a necessity at all Alamos operations. Our internal Non-Hazardous & Hazardous Waste Management Standard and Mine Ore & Waste Stockpile Management Standard apply to all sites and define the minimum requirements to manage waste in accordance with our values. The Non-Hazardous & Hazardous Waste Management Standard stipulates that: hazardous and non-hazardous waste, including domestic waste, must be separated and labelled prior to storage and disposal; all on-site waste storage facilities align with leading industry practices (such as secondary containment and coverage) and applicable legislative requirements, and; the transportation and offsite disposal of waste must be carried out within 90 days of the generation date by licensed contractors. The Mine Ore & Waste Stockpile Management Standard stipulates that sites must: assess the potential for acid generation and the leaching of metals at all stockpiles; assess the geotechnical and seismic stability of stockpiles with a life of longer than one year; construct, operate, maintain, and monitor stockpiles in a manner ensuring long-term geotechnical stability, and; develop and maintain site-specific Mine Ore and Waste Stockpile Materials Management Plans that establish relevant internal procedures and responsibilities. Each site has its own waste management program in place to ensure that these stipulations, alongside any additional jurisdictional requirements, are satisfied by both Alamos and our third-party waste management suppliers – at all stages of the mine life cycle.

As a general rule, Alamos seeks to reduce the amount of waste produced at our mines. The negative impacts associated with waste generation are caused both directly by Alamos (such as increased safety risks from on site waste storage) and indirectly through our value chain (such as increased land use by landfills and emissions from off-site incineration). To reduce waste generation at our sites, we procure materials to meet our operational demands. To lessen the impact of generated waste at our operations, waste is recycled whenever possible. In 2023, Young-Davidson circulated an updated Refuse Management Plan across the site, outlining the proper flow of waste and recyclables from source (both surface and underground) to final disposal. Details surrounding waste categorization, sorting protocols, bin locations, and the roles and responsibilities of all parties were made clear to ensure waste is managed with a reduction mindset. Island Gold is also bringing attention to the importance of waste reduction, re-use, and recycling (the 3 Rs), having implemented an employee-led 3 Rs Sub-committee in 2023.

Waste Management Metrics (Tonnes)

Table 5.11

| Type of Waste | Young-Davidson | Island Gold | Mulatos | Alamos Total: 2023 |

Alamos Total: 2022 |

Alamos Total: 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NON-MINERAL WASTE | ||||||

| Non-Hazardous Waste Disposed25 | 458 | 3,131 | 590 | 4,179 | 3,750 | 3,574 |

| Non-Hazardous Waste Recycled/Reused | 792 | 909 | 655 | 2,356 | 2,712 | 2,367 |

| Hazardous Waste Disposed | 37 | 167 | 469 | 673 | 716 | 516 |

| Hazardous Waste Recycled/Reused26 | 30 | 95 | 471 | 596 | 496 | 628 |

| Total Non-Mineral Waste Generated | 1,317 | 4,302 | 2,186 | 7,805 | 7,674 | 7,085 |

| % Non-Mineral Waste Recycled/Reused | 62.4% | 23.3% | 52.5% | 37.8% | 41.8% | 42.3% |

| MINERAL WASTE27 | ||||||

| Non-Hazardous Waste Rock Disposed (NPAG)28 | 451,287 | 482,598 | 785,874 | 1,719,759 | 6,134,320 | 6,805,265 |

| Non-Hazardous Waste Rock Recycled/Reused | 377,255 | 363,205 | 0 | 740,460 | 1,686,618 | 437,942 |

| Hazardous Waste Rock Disposed (PAG)29 | 0 | 0 | 22,592,179 | 22,592,179 | 24,392,920 | 23,953,694 |

| Tailings Disposed30 | 2,878,047 | 439,008 | 0 | 3,317,055 | 3,291,903 | 3,315,839 |

| Hazardous Mineral Waste Recycled/Reused31 | 1,662,950 | 0 | 0 | 1,662,950 | 0 | 0 |

| Total Mineral Waste Generated | 3,329,334 | 921,606 | 23,378,053 | 27,628,993 | 35,505,761 | 34,512,740 |

| TOTAL MINERAL AND NON-MINERAL WASTE DISPOSED, RECYCLED, AND GENERATED | ||||||

| Total Waste Disposed32 | 3,329,829 | 924,904 | 23,379,112 | 27,633,845 | 33,823,609 | 34,078,888 |

| Total Waste Recycled/Reused | 2,041,027 | 363,209 | 1,126 | 2,405,362 | 1,689,826 | 440,937 |

| Total Waste Generated33 | 3,330,651 | 925,908 | 23,380,239 | 27,536,798 | 35,513,435 | 34,519,825 |

| % Waste Recycled/Reused | 61.2% | 39.2% | 0% | 8.7% | 4.8% | 1.3% |

Company-Wide Waste Generation vs Waste Recycling/Reuse (tonnes)

Figure 5.4

Waste is deemed hazardous if it possesses properties that can be harmful to the health and safety of people or the natural environment. All staff who interact with hazardous waste are trained in proper storage and handling techniques, and the risks associated with hazardous waste are considered in our routine health and safety risk assessments on site. Each site maintains its own Spill Response Procedure which outlines the process for safely addressing and remediating spills.

In 2023, one reportable spill of hazardous material occurred at Island Gold (see Table 5.12). The impacted area was remediated with no anticipated long-term effects.

Reportable Spills

Table 5.12

| Location | Material | Volume | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Island Gold | Fuel | 0.5L | A temporary sheen was visible on Maskinonge Lake. The fuel was absorbed and the water contained no contaminants of concern per the post-cleanup sample and analysis. |

Nature

Mining can have profound impacts on nature, both locally and in broader contexts. In terms of direct local impacts, the construction and operations phases of the mining lifecycle can alter terrestrial and aquatic habitat and airways, which can result in local species reduction as well as other general changes to ecological processes that are outside of the natural range of variation. Based on the amount of surface area impacted, direct habitat conversion is inherently more consequential at open-pit mines (such as the Mulatos mine) than underground mines (such as the Young-Davidson and Island Gold mines). In the broader context of indirect impacts, emissions from mining activities contribute to climate change, which can alter habitats globally.

IUCN Red List Species Potentially Impacted by Operation

Table 5.13

| Classification | Operations: Young-Davidson |

Operations: Island Gold |

Operations: Mulatos |

Projects: Lynn Lake |

Projects: Türkiye Combined Projects |

Closure: El Chanate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critically Endangered | 134 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 235 | 136 |

| Endangered | 137 | 238 | 339 | 240 | 141 | 0 |

| Vulnerable | 2 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 0 |

| Near Threatened | 1 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 3 |

| Least Concern | 159 | 29 | 259 | 11 | 154 | 48 |

| Ecosystem Containing Endangered Species (High Biodiversity Value) | Freshwater & Terrestrial | Terrestrial | Freshwater | Freshwater & Terrestrial | Freshwater & Terrestrial | Terrestrial |

While potentially-affected species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN’s) Red List have been reported in Table 5.13, our operations track and manage species at risk in accordance with their respective jurisdictional requirements per Table 5.14.

Species at Risk per Jurisdictional Regulation

Table 5.14

| Classification | Operations: Young-Davidson |

Operations: Island Gold |

Operations: Mulatos |

Projects: Lynn Lake |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulation | Canada’s Species at Risk Act Ontario’s Endangered Species Act |

Canada’s Species at Risk Act Ontario’s Endangered Species Act |

Ley General de Vida Silvestre NOM-059-Semarnat-2010 |

Canada’s Species at Risk Act Manitoba’s Endangered Species and Ecosystems Act |

| Endangered | 342 | 243 | 344 | 245 |

| Threatened | 246 | 147 | 848 | 649 |

| Special Concern | 350 | 151 | 1052 | 753 |

The Young-Davidson mine is situated adjacent to the protected West Montreal River Provincial Park, and the Mulatos mine contains a portion of the protected Mulatos River. As all Alamos sites (and 100% of our proven and probable mineral reserves) are located within or near either endangered species habitat or protected conservation areas, we are mindful of our direct impacts on nature. Our internal Biodiversity and Land Use Standard applies to all Alamos operations. The Standard stipulates that prior to any new surface disturbance, authorization must be sought from the Environmental department (who are responsible for securing all relevant permits), and an assessment of potential impacts to cultural resources, traditional knowledge, territorial lands, archeological features, listed wildlife and vegetation species, sensitive areas, sensitive habitats, and wetlands must be conducted. The Standard also requires that sites minimize ecosystem disturbance to only what is essential for safe and efficient operations, and that they control the influence of introduced species – particularly invasive plant species, weeds, feral predators, and plant and animal diseases. Further, working closely with environmental professionals and local authorities, Alamos applies the Mitigation Hierarchy principles in seeking to avoid, minimise, restore/rehabilitate, or offset our impacts wherever possible.

In 2023, Alamos continued working towards our goal of implementing a Biodiversity and Land Use Management Plan (BLUMP) at each of our operating sites. The BLUMP at Island Gold is complete, and those of Young-Davidson and Mulatos are underway. These BLUMPs will aim to outline procedures and processes to ensure the protection of fragile ecosystems, habitats, and endangered species in the specific context of each site. While our policies and practices were not specifically developed to satisfy the IFC’s Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability, they are aligned with the general themes of Performance Standard 6: Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Management of Living Natural Resources.

Land Use (ha)

Table 5.15

| Purpose of Land | Operations: Young-Davidson |

Operations: Island Gold |

Operations: Mulatos |

Projects: Lynn Lake Project |

Closure: El Chanate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size of Operation54 | 1,413 | 1,375 | 22,678 | 1,172 | 2,806 |

| Area Disturbed During the Year | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Area Rehabilitated During the Year | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Total Area Disturbed and Unrehabilitated at Year-End | 432 | 235 | 1,058 | 166 | 116 |

While our business has inherent effects on nature for the duration of the life-of-mine, a number of these effects are positive. For example, the water discharged from our sites is often of higher quality than the baseline quality of the area. At Young-Davidson, Alamos has seeded and covered historic mine tailings located within the property to reintroduce vegetation to what was previously unusable land. Further, many of the negative impacts of mining are temporary and addressed during the closure and reclamation phases of the mine life cycle. In keeping with our company-wide Mine Closure Standard, all of Alamos’ mines are equipped with a closure plan and are considered in our Asset Retirement Obligation (ARO) exercise, which helps to fulfill our legal obligation in Canada to set aside sufficient funds for the decommissioning and reclamation of every mine we operate. Closure Plans and the ARO are annually reviewed, with budgets being independently examined. We frequently update our closure plans in accordance with legislative requirements and leading industry practices. Alamos aims to practice progressive reclamation wherever possible, by restoring disturbed land as soon as it is no longer required. The ways in which we restore these lands are being increasingly influenced by our communities of interest. Our objective in closure is to rehabilitate our sites to an ecologically healthy state that is agreed upon by local stakeholders.

NATURE SPOTLIGHT

Read More

In 2023, the Mulatos mine implemented an inter-community beekeeping project wherein 12 apiaries containing a cumulative 60 hives were introduced. Nine families and one school volunteered to host the apiaries, and each were provided with all of the necessary tools, gear, personally protective equipment (PPE) and training for successful beekeeping. The project comes at a time of global pollination crisis: populations of pollinator species have been facing concerning declines, and approximately 70% of major food crops require pollination. Providing this new productive habitat is not only beneficial environmentally – the hosts of the apiaries may also benefit economically from the hives’ products (honey, wax, royal jelly, api-toxin, etc.). Apiaries were also introduced at Mulatos and La Yaqui Grande, supporting the growth of trees, flowers and plants across the site.

Air Quality

Alamos conducts air quality monitoring at all operations to protect both human and environmental health, and to comply with all relevant jurisdictional requirements. Our Canadian operations are subject to the requirements of their Environmental Compliance Approvals (ECAs) for Air and Noise granted by the province of Ontario’s Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks. They are also federally required to annually report significant air emissions to the National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI). Mexican regulation does not possess these requirements, thus while the Mulatos Mine does track air emissions as required, it does not comprehensively track Persistent Organic Pollutants (POP), Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC), Hazardous Air Pollutants (HAP), PM2.5, Carbon Monoxide (CO), Lead (Pb), or Mercury (Hg).

Significant Air Emissions (tonnes)

Table 5.16

| Type of Emission | Young-Davidson | Island Gold | Mulatos | Alamos Total: 2023 |

Alamos Total: 2022 |

Alamos Total: 202155 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOx | 28.1 | 440.2 | 4,402.0 | 4,870.3 | 4,844.0 | 4,417.0 |

| SOx | 0.2 | 0.7 | 18.9 | 19.8 | 15.4 | 15.0 |

| POP | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | – |

| VOC | 31.6 | 8.5 | – | 40.1 | 42.9 | – |

| HAP | 38.5 | 0.4 | – | 39.0 | 39.5 | – |

| PM10 | 8.6 | 83.2 | 147.7 | 239.5 | 226.8 | 187.0 |

| PM2.5 | 2.6 | 61.6 | – | 64.2 | 60.0 | – |

| CO | 187.6 | 322.2 | 1,157.6 | 1,667.4 | 582.0 | – |

| Pb | 0.00000 | 0.00033 | – | 0.00033 | 0.00123 | – |

| Hg | 0.00000 | 0.00002 | – | 0.00002 | 0.00000 | – |

References

Footnotes

- https://www.ieso.ca/en/Learn/Ontario-Electricity-Grid/Supply-Mix-and-Generation ↩

- Within the organization. Energy consumption outside of the organization is not tracked. ↩

- A portion of Heavy Fuel Oil is combusted in explosives and considered “stationary combustion” ↩

- Heavy Fuel Oil, Propane, and Compressed Natural Gas are indicative of energy used for heating. Alamos does not consume steam. Cooling is untracked and a component of our electricity use. ↩

- Heavy Fuel Oil, Propane, and Compressed Natural Gas are indicative of energy used for heating. Alamos does not consume steam. Cooling is untracked and a component of our electricity use. ↩

- Alamos does not sell electricity. ↩

- Excludes Electricity Generated at Mulatos, as this is included within Petroleum Diesel subtotal. ↩

- Includes only energy use within the organization, from all energy types included in Energy Consumption table. ↩

- The 2021 values for Water Discharged, Water Consumed, Water Used, Portion of Water Recycled/Reused, and Water Intensity have been restated on account of water discharges having been under-reported for the Mulatos Mine in years prior. ↩

- Ore that is milled or stacked. ↩

- No Alamos operation uses Mercury (Hg) in the processing of gold. ↩

- No water is withdrawn or discharged to water stressed areas. ↩

- 100% of Young-Davidson water withdrawals are freshwater (<1000mg/L Total Dissolved Solids) ↩

- 0% of Young-Davidson water discharges are freshwater (<1000mg/L Total Dissolved Solids) ↩

- Cubic meter of water consumed per tonne of ore treated. ↩

- No water is withdrawn or discharged to water stressed areas. ↩

- 41% of Island Gold’s water withdrawals are freshwater (<1000mg/L Total Dissolved Solids) ↩

- 98.8%% of Island Gold’s water discharges are freshwater (<1000mg/L Total Dissolved Solids) ↩

- Cubic meter of water consumed per tonne of ore treated. ↩

- Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas (wri.org) ↩

- No water is withdrawn or discharged to water stressed areas. ↩

- 100% of Mulatos’ water withdrawals are freshwater (<1000mg/L Total Dissolved Solids) ↩

- 100% of Mulatos’ water discharges are freshwater (<1000mg/L Total Dissolved Solids) ↩

- Cubic meter of water consumed per tonne of ore treated. ↩

- Sent to off-site landfills for Young-Davidson and Island Gold, and to an on-site landfill at Mulatos. ↩

- Used oil, sent for off-site treatment or used on-site as fuel. ↩

- For mineral waste, disposal refers to safe on-site storage for eventual remediation. ↩

- Non-Potentially Acid Generating Waste Rock. ↩

- Potentially Acid Generating Waste Rock. ↩

- All Tailings are considered hazardous. ↩

- Tailings used as paste fill. ↩

- Includes dominantly mineral waste stored on-site. See Non-Mineral Waste disposal totals for total waste sent to landfill. ↩

- Note that the Total Waste Generated figures are not the sum of the two rows above, as much of the mineral waste reused in 2023 (applied on site for construction or back-filling purposes) was generated in previous reporting years. ↩

- Black Ash (Fraxinus nigra) ↩

- Snowdrop (Galanthus trojanus) and European Eel (Anguilla anguilla) ↩

- Mojave Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) ↩

- Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus) ↩

- Eastern Small-footed Bat (Myotis leibii) and Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus) ↩

- Gila Chub (Gila intermedia), Headwater Livebearer (Poeciliopsis monachal), and Yaqui Catfish (Ictalurus pricei) ↩

- Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus) and Lake Sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) ↩

- Steppe Eagle (Aquila nipalensis) ↩

- Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus), Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus), Northern Myotis (Myotis septentrionalis) ↩

- Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus) and Northern Myotis (Myotis septentrionalis) ↩

- Gila Chub (Gila intermedia), Yaqui Chub (Gila purpurea), Sonora Sucker (Catostomus insignis) ↩

- Little Brown Bat (Myotis lucifugus) and Northern Myotis (Myotis septentrionalis) ↩

- Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) and Black Ash (Fraxinus nigra) ↩

- Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis) ↩

- Longfin Dace (Agosia chrysogaster), Rio Grande Sucker (Catostomus plebeius), Yaqui Catfish (Ictalurus pricei), Gila Topminnow (Poeciliopsis occidentalis), Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Lithobates chiricahuensis), Blackneck Garter Snake (Thamnophis cyrtopsis), Sonoran Coral Snake (Micruroides euryxanthus), Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis) ↩

- Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou), Common Nighthawk (Chordeiles minor), Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus), Olive-sided Flycatcher (Contopus cooperi), Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia), Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica) ↩

- Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), American Bumble Bee (Bombus pensylvanicus), and Rusty Blackbird (Euphagus carolinus) ↩

- Yellow-banded Bumble Bee (Bombus terricola) ↩

- Yaqui Sucker (Catostomus bernardini), Tarahumara Salamander (Ambystoma rosaceum), Madrean Alligator Lizard (Elgaria kingii), Northern Pigmy Skink (Plestiodon parviauriculatus), Black-tailed Rattlesnake (Crotalus molossus), Montezuma Quail (Cyrtonyx montezumae), Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii), Common Black Hawk (Buteogallus anthracinus), Swainson’s Hawk (Buteo swainsoni), Brown-backed Solitaire (Myadestes occidentalis) ↩

- Wolverine (Gulo gulo), Yellow Rail (Coturnicops noveboracensis), Evening Grosbeak (Coccothraustes vespertinus), Rusty Blackbird (Euphagus carolinus), Northern Leopard Frog (Lithobates pipiens), Yellow-banded Bumble Bee (Bombus terricola), and Transverse Lady Beetle (Coccinella transversoguttata) ↩

- For the purposes of representing Alamos’ land use, this figure includes all land inside each site’s most recent Closure boundary (the area Alamos may be responsible to rehabilitate at the end of the life of mine). Note that this entire area will not necessarily be disturbed/altered. ↩

- POP, VOC, HAP, PM2.5, CO, Pb, and Hg were reported for the first time in 2022. ↩